A Condensed History of Australian Camels

Who are we, who is each of us, if not a combinatoria of experiences, information, books we have read, things imagined? Each life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, a series of styles, and everything can be constantly shuffled and reordered in every way conceivable.

Italo Calvino

The details have the impress of the originating reality; and for all their fictional ‘panache,’ the artworks that get brewed from the details still display a staunch allegiance to something real.

Ross Gibson

…silence does not always exist to be filled; sometimes it should be interrogated.

Ambelin Kwaymullina

It seems that the harmony between the total landscape and all of the elements within have realised that this animal is incongruous with the whole. And for this reason they now perform silence; they discontinue their exuberance.

Behrouz Boochani

Like a tropical storm,

I, too, may one day become “better organized.”

I, too, may one day become “better organized.”

Lydia Davis

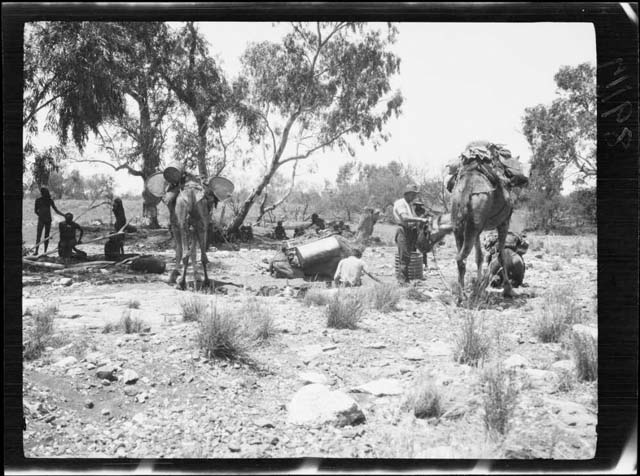

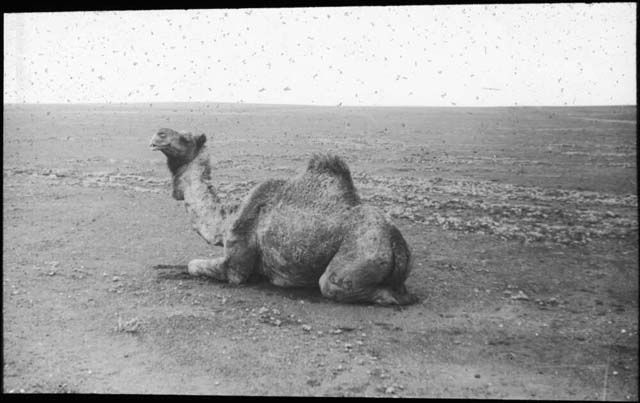

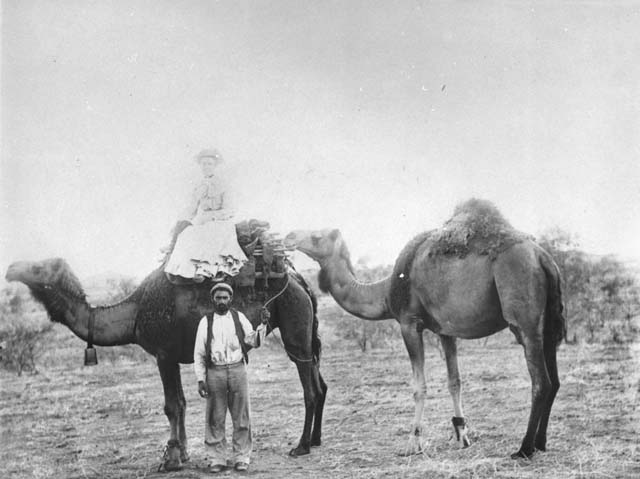

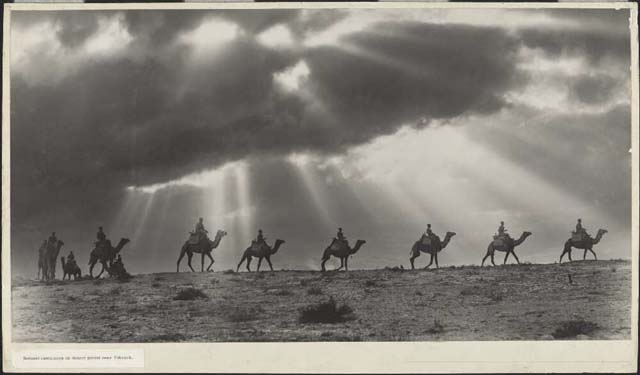

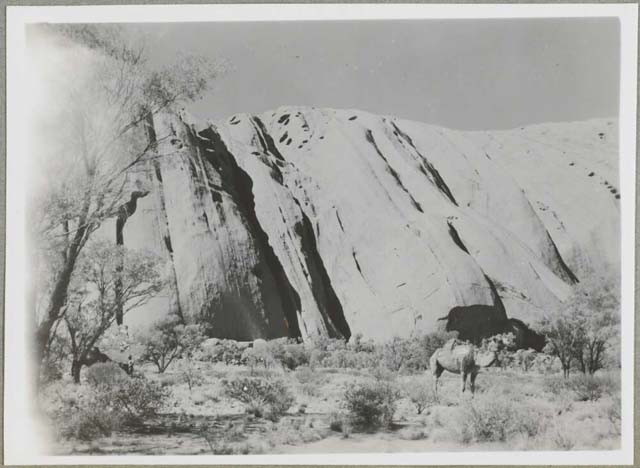

Surveying the Australian landscape and archive, one sees camels everywhere.

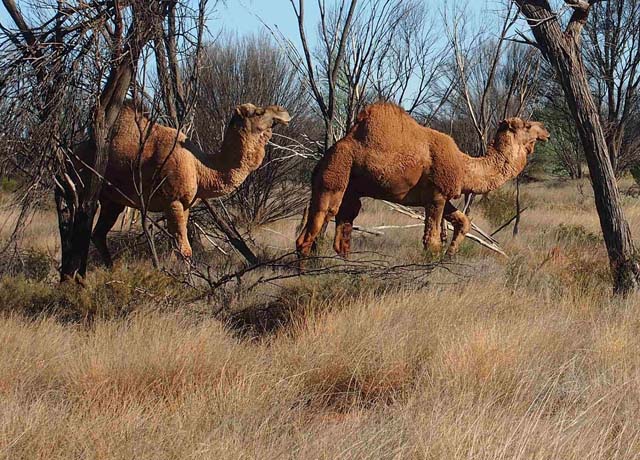

The camel is not indigenous to Australia. It is feral. Feral here. It came by boat. It is regarded as a beast, a pest, a problem. Current solutions involve ammunition and helicopters, business proposals and conservation, research and governance.

The camel is the story of various Australias. The story of arrival. Invasion. Exploration, immigration, colonisation, war… It is a prism through which iridescent fragments of Australia can be viewed.

![(1893) ‘Unloading camels at Port Augusta [B 68916]’, Port Augusta Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1893) ‘Unloading camels at Port Augusta [B 68916]’, Port Augusta Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image3.jpg)

It is also just a hairy animal with four legs, two eyes, two nostrils, and one hump. Sometimes two.

First Camel

F bent his front knees and sat. Though this caused increased whipping of his rear and shouting, these discomforts were familiar and therefore preferable to the unsteadiness of the gangway.

![East Melbourne (Vic.): Herald Office (1861) ‘[Camels disembarking]’, Accession# NLA00/12/61/1, Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC. East Melbourne (Vic.): Herald Office (1861) ‘[Camels disembarking]’, Accession# NLA00/12/61/1, Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC.](img/docmedia/image4.jpg)

With or without Camel F, the S.S. Apolline was to leave Santa Cruz de Tenerife in thirty minutes. Camels A, B, C, D, and E were already on board, packed into their respective pens. A suggestion germinated amongst the Apolline’s crew to leave F behind. ‘We will just say he died at sea.’ This was overheard by Captain William Deane, who, wary of his crew attempting to cut corners before the voyage had even begun, ordered everyone drop what they were doing and attend to the animal. ‘Carry him if need be!’

A rope was tied to F’s neck. F felt firm tugs and heard stomping boots, unified by grunting. His neck lunged. F rose and pulled, resisting strain. His muscles hyperextended, vocal folds vacillated, and ligaments stretched beyond capacity. F lost balance, the tug-of-war, and the will to resist. Sore and terrified, he was hauled onto the ship by his now-tender neck and wrenched along to the animal pens. A gate opened, revealing D and E: two other males. D and E were so confined that their only response was to blink thick, hairy eyelids. F was wedged in. The gate pressed closed in his face.

Ground moved. Light disappeared. A zigzagging ache throbbed through F’s neck. He tried to relieve the pain by standing, but his hump and head bumped roof, forcing him back down. Every time this happened, F groaned. His groans caused shouting and rapping on the pen walls.

Light returned. Grain fell into the pen. Water poured into the trough. Urine dripped down F’s hind legs. Due to the position of his neck, F could not easily eat or drink. His hump wilted.

A suggestion germinated amongst the ship’s higher-paying passengers to let the camels out in the hope that a bit of exercise might help them stay quiet at night. Captain Deane allowed it. At dusk, the pens were opened, and ropes were tied to the camels’ necks. A, B, C, D, and E stood and strode out with little encouragement, but F, despite twitches of the rope, simply rolled onto his side and refused to stand.

A, B, C, D, and E were dressed in pretend crowns and gowns, announced as ‘Kings and Queens of Ancient Lands,’ and paraded around the Apolline’s deck. Their legs were as uneasy as newborns’, yet they roared with pleasure as their cramped muscles stretched. The wind also roared. The watching passengers waved, blew kisses, and laughed. The Apolline tilted. B and C lost their footing. Legs entwined, sprained, collapsed. Camel and human bones snapped. Members of both species howled. As the ship equalised, A, C, and D managed to stand. B and E remained on their backs, blood and urine pooling beneath exposed bone.

The paying passengers were calmed and returned to their cabins. A, C, and D were calmed and returned to their pens. An injured seaman’s leg was put in a bandage, and he to bed. B and E were put to sleep, and their corpses butchered.

Captain Deane passed a rule forbidding the release of camels at sea.

That night the smell of stewing camel meat wafted out of the galley and combined with the salty air. The odour made F moan louder than ever. No amount of shouting or rapping of the walls could quiet him.

E’s death allowed F movement. F began bobbing his head, rocking from side to side, chewing the pen mesh, crying out for space, sleep, salt, crunch, friction, firmness, a horizon. The only break in the monotony was the occasional mopping of urine and faeces, and the dispensing of grain and water. When food arrived, F nipped at D. At first this started as a game, with F playfully gumming D’s neck, but as weeks of boredom corroded any other purpose the playful fight for food took on enormous significance. F’s biting became savage. On occasion he broke skin.

As the ship continued south, the temperature dropped. F went into rut. His tail and gums flapped. Saliva foamed. His dulla inflated and dangled out his mouth: a dripping, frothy, membranous blob. F rose, lifting the roof with his flabby hump. He bellowed, urinated, bucked, bit, broke the pen’s gate and D’s bones, burst onto the deck with a staggering gallop, knocked over men and the female pen, roared, fell, got up, fell, was pinned down, rolled over, crushed bone, howled in response to yelping men.

F was eventually detained. The gate was repaired and fortified. D was slaughtered and eaten. A crewman’s forearm was amputated.

A fear germinated amongst the ship’s crew that F had an exotic, rabies-like disease which caused his inner organs to leap out his mouth. From his stretcher, the one-armed crewman groggily suggested F be put down. ‘Make it as painful as possible,’ he said. This was overheard by Captain Deane who, wary of his crew becoming disgruntled, asserted that F was just displaying normal mating behaviour and that they were required to arrive in Australia with at least one male and female so that a breeding program could be established. ‘Think of us as you would Noah’s Ark.’

The ship continued south. Three passengers complained of pains in their chests. Two turned yellow and fell unconscious. All held F responsible. Against Captain Deane’s orders, the crew ceased feeding the camels.

F’s hump faded. He came out of rut. His ribs appeared. His faeces liquefied. He groaned for food. His groans did nothing. They did not even cause shouting or rapping of the pen walls.

Camels A and C died. At Captain Deane’s request, the ship’s surgeon performed an autopsy of their carcasses. He discovered A and C’s inner organs covered with apple-sized cysts, and their stomachs filled with faeces. A and C’s bodies were tossed overboard.

Captain Deane passed a rule forbidding the consumption of camel meat.

On October 12th, 1840, the S.S. Apolline arrived at Port Adelaide. F was dragged out of the soiled pen, down the gangway, and onto Australian ground. Like a calf, his cautious limbs faltered at first, but within minutes F was taking lengthy strides, absorbing alien smells, experiencing bygone pleasures: the pleasure of putting one foot in front of the other, of stiffness crackling out joints, of blowing crusted salt from nostrils, of a quickened heartbeat.

F’s pleasure was halted by whips that forced his front knees to bend and his body to lower. A strange-smelling crowd clustered. Threatening fingers pointed. Aciculate whispers made his ears twitch. A squeaking child waddled over and slapped its palms on F’s hide. ‘Mummy! Funny horsey! Funny horsey!’ F turned and bit the child’s head. This caused a punishing sound so loud F leapt up and galloped. Despite malnourishment, F overpowered the resisting rope and ran from the sound, the ship, the whips, the people, the scaffolding, roads, houses, farms, his own faeces, the rope that trailed him, the crackle of distant thunder. He ran towards a billabong and gulped. He ran towards shadows and slept. He ran towards foliage and chewed. He ran for the pleasure of running.

Light disappeared. Light returned. F’s hump returned. His faeces firmed. His ribs disappeared behind fat. Nothing he did caused shouts or whips.

The temperature dropped. F again went into rut. He bellowed at the infinite landscape. Hormones swarmed his system. Like the claustrophobic boredom of the Apolline’s pen, the emptiness of the unending desert offered nothing. F began bobbing his head, rocking from side to side, chewing the rope around his neck, crying out for females, other camels, interaction.

F was discovered by a farmer, who captured and confined him to a paddock. The farmer was delighted to have finally solved the mystery of the ‘bellowing bunyip’ that had been scaring his daughter at night. His daughter was also relieved, until she approached F and received a brutal bite to the head.

F’s snout was bound with rope. His breathing became shallow. F attempted to roar in protest, but produced only hums. The inability to extend his jaw filled F with an urge to bite. Not due to hunger, but for the sensory pleasure of pressure on teeth. He attempted to slide the muzzle off by wiping his face on the paddock gate but managed only to embed a splinter in his eyelid. F thrashed. His eye flooded. Vision blurred. Periphery dissolved. The splinter and muzzle remained.

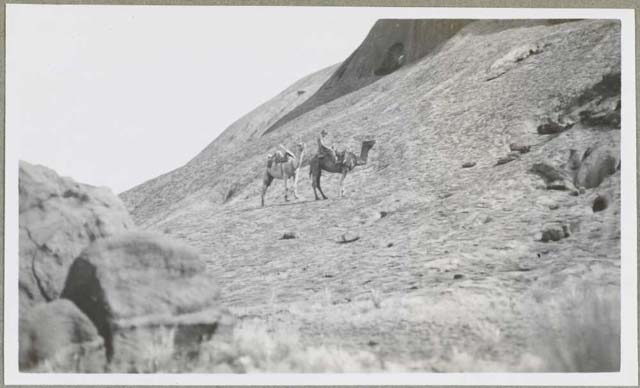

With minimal negotiation, the farmer sold F to the pastoralist and explorer John Ainsworth Horrocks. Horrocks christened the camel ‘Harry.’

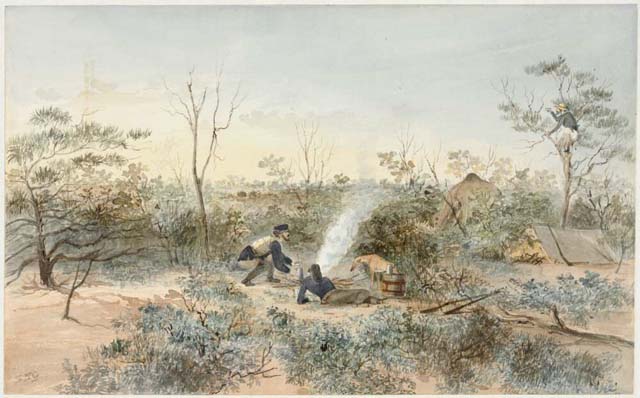

![Gill, S.T. (1846) ‘[Salt Lake, N.W. of Mt Arden, Horrocks’ N.W. Expedition] [B 72813]’, Horrocks Expedition Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. Gill, S.T. (1846) ‘[Salt Lake, N.W. of Mt Arden, Horrocks’ N.W. Expedition] [B 72813]’, Horrocks Expedition Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image6.jpg)

F’s entire body was bound, and a discouraging pressure applied to his back. Despite whips and shouts, he refused to stand. This refusal caused an intolerable jab to his rear, which forced him to his feet. F’s quivering legs barely coped.

Every footstep now demanded maximum effort, as if wading through never-ending marsh. If F tried to stop, the sharpness in his rear returned. Walking made him so exhausted he barely absorbed his surroundings. He snapped at any blurs that passed before his damaged vision. Doing so produced excruciating, inescapable screeches.

When the forced walking ceased, F dozed. When food was presented, F grazed. When water was offered, F guzzled. Hump and energy faded. Endurance was fed only by a flicker of terror.

At the hottest part of the day, F was uncharacteristically halted. As soon as his body lowered, he shut his eyes and collapsed. F felt a calming, silent emptiness. He heard a non-threatening twittering. This was interrupted by the sound of the sharpest tooth scraping stone. F jolted, lurching at the sound. Doing so produced the loudest, most cacophonous thunder.

The right barrel of John Ainsworth Horrocks’ gun discharged, taking off the middle finger of his right hand, dislodging seven teeth from his upper jaw, and bringing an early end to his expedition. Bernard Kilroy, a member of Horrocks’ party, was dispatched to fetch help. Samuel Thomas Gill, the party’s artist, tended to Horrocks’ wounds. Horrocks remained on the ground, dripping with agony. He glared at the camel, attempting to will his pain onto the beast. The camel displayed no remorse, guilt, or acknowledgement of what he had done. He just went back to sleep. ‘Harry’ was supposed to have facilitated desert exploration, opened up new agricultural possibilities, and illuminated the Australian landscape. Instead, while Horrocks had prepared his gun to shoot a bird for the Natural History Collection, the camel had inadvertently lunged, causing Horrocks to shoot himself in the face.

The expedition turned around, traveling for days without rest. Horrocks was returned to his Penwortham cottage and put to bed. His physician, Doctor Nott, arrived from Adelaide and looked him over. Nott offered only pleasantries and basic treatment. Horrocks was not sure if he heard or imagined the word ‘gangrene.’ He was not sure if he smelled or imagined a putrefactive scent. He was not sure if what he was experiencing was real, so frequently did he dissolve in and out of consciousness. One moment he was vomiting into a basin, the next he was thirteen, back in Boulogne, giving a piano recital. His performance was going poorly. Despite repeatedly striking the keys, his instrument produced no sound. This so infuriated Horrocks’ tight-lipped tutor that she barged through the crowd and slammed the fall board on his hands. Horrocks gasped. Hot air excited his exposed nerves, stinging him so painfully his purulent eyelids ripped apart. He blinked thick, gooey blinks. The room’s curtains were haloed blue. Horrocks was not sure if it was sunset or sunrise. His back and groin were greased with sweat. His hair stuck to his forehead in clumps. Horrocks was not sure if this was due to the weather or fever. His wrist throbbed a dull rhythm, accompanied by involuntary jerks. His nightmare had not been particularly frightening, but upon re-establishing that one of his fingers was missing, he started to hyperventilate. He attempted to call for help, but his flailing tongue produced only glottal tones. He tried to steady his breathing, forming his scaly lips into an ‘O,’ enabling him to extend his exhalations. With his left hand he grappled at the side table. He felt for a pen. Bending torso forward, concentrating vision, and steadying hand, Horrocks dipped his pen into the inkwell before attempting to write: I want Harry to die before I do.

The temperature dropped. F did not go into rut. Despite hearing what sounded like the distant mating calls of other camels, his dulla remained shrivelled. F was dragged past smells, people, and paddocks, to the top of a hill. The sun made him blink. Blinking made him grunt. F heard teeth scrape stone. He bent his knees and sat. He heard the loudest thunder. Felt bursting, leaking, numbness, the ground, sleep. Heard more scraping teeth, more thunder.

Then nothing.

![Teague, V. (1933) ‘Camel – head studies, [N.T.]’, Accession# H2010.123/49, Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC. Teague, V. (1933) ‘Camel – head studies, [N.T.]’, Accession# H2010.123/49, Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, VIC.](img/docmedia/image8.jpg)

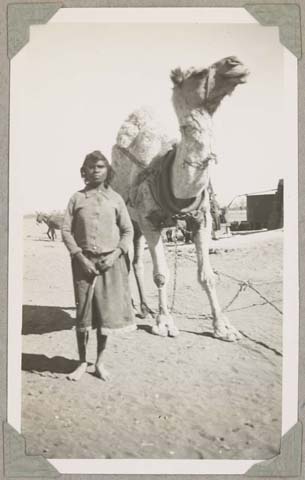

If one researches Indigenous photographs in Australian archives, one is notified that Indigenous works may have additional legal and cultural issues, and one may need to seek cultural clearances from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, families, individuals and organisations. If one comes across an old image one wishes to use, such as the photograph of the Indigenous woman with the camel displayed below, one is advised to contact the library to check for cultural clearances to ensure that the publishing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material is ethical.

In doing so, the ambitious, naïve, non-Indigenous researcher hopes to become involved with Indigenous communities, to learn the oldest histories, to engage with the broadest dialogue. After going through the recommended process, however, a curt email is sent that informs:

…given the content of the images, the recommendation is that you include a cultural sensitivity warning in your publication (i.e. that the publication includes images of people who have died).

This has been done. It feels merely like a protective umbrella from cultural and legal accusations, like so many other mutes in the horn of the Indigenous voice.

To not include is to disregard. To include is to assume. In a world of saturated media and information, in these constructed, meta-fictional, hyper-alert times, should respect be given to inclusion or silence?

Design by Committee.

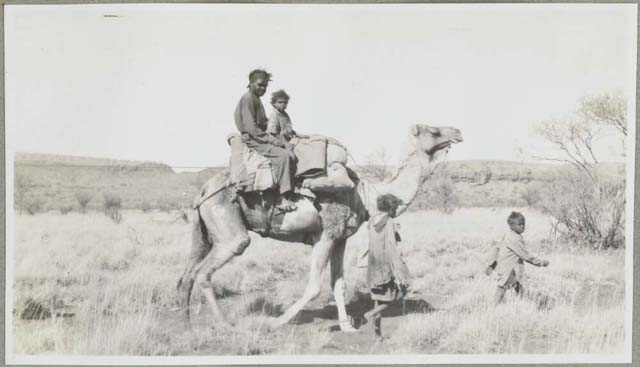

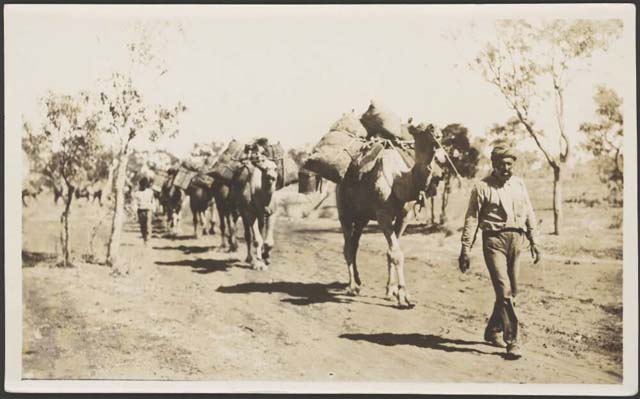

Two children, likely girls, each lead a camel. The children are bare-footed, wearing wide-brimmed hats.

One child faces forward, walking with a confident gait, pulling the rope tight, which causes the camel to lean its head forward. This child conceivably experiences a unique sense of responsibility, as she is leading both the camel and the group.

The second child looks back at her camel. This child’s rope is less tight. Her leg is raised as if ready to run. She appears wary that her power over the animal is an impression only.

The two camels are dromedaries. One has thicker hair than the other. Neither animal appears malnourished, though the lighter camel has a slightly wilted hump and almost visible ribs.

Behind the camels, at the end of taut ropes, is a horse carcass. Its body is dragged without much difficulty; the camels do not strain. The dead horse has no markings, and is likely a wild horse captured in accordance with a measure advocating the culling of brumbies, after The Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News described the ongoing increase of feral horses or ‘brumbies’ as “A NUISANCE of no slight present importance to the breeders of horses, and which will probably hereafter prove to be a serious drawback, unless some measure is taken for its abatement.” (1850, 15 March, p.2).

The ground is dusty and dry. The landscape is arid. Beside the convoy, there are parched trees with wiry branches.

Finally, beside the camels, overlooking the animals and the children, is a man. He wears a broad hat, a white shirt with rolled up sleeves, and pants. He may or may not be wearing footwear. He is an Indigenous Australian. This fact cannot be ignored. The archive has labelled him an ‘Aboriginal man’. No specific Indigenous community is specified.

A story of this man’s experience could be told here. Many would see no issues with the heroic depiction of a man struggling against nature, in either the bringing down or retrieving of the dead brumby, coupled with his care for these two children. Or perhaps this story could indulge in a romantic view of the outback Australian landscape. Or perhaps it could detail a personal epic of this individual in the Australia of the early 20th Century. All of these could be potentially persuasive in the literary realist tradition that has characterised much of Western literature since the end of the 18th century.

The origin of the word ‘brumby’ is obscure and hard to pin down. The term means ‘wild horse’, but also simply and figuratively ‘wild’. In 1804, a Sergeant James Brumby, when he went to Tasmania, left horses at his property at Musgrave Place. A Mr Brumby near Canberra supposedly did likewise. A stock of horses was reported to have been abandoned in the Burnett district of Queensland, at a creek and station called Baramba; it has been argued that this is where the term comes from. The Irish word for ‘colt’ is bromach. Earlier iterations use not the word ‘brumby’, but ‘brummy’, derived from Brummagen, a variation of ‘Birmingham’, the meaning of which later came to mean a ‘sham’ or ‘counterfeit’. E.E. Morris, in Austral English (1898), proposes that the origin of the word is Indigenous, stemming from the Pitjara word baroomby, meaning ‘wild’. The origin of the word, however, may be none of these things.

So it is with this man. While this viable brumby culler could be resurrected by words typed into a computer and printed on pages, while such a structure and depiction could appear truthful and persuasive to some non-Indigenous and Indigenous readers, there is much of this man’s interior life that would not be dramatized: a hypothetical hidden retrospective fountain of experience, an unseen ocean of remembrance capable of internal strength and illumination that goes beyond the introduction of camels to Australia. All of this may or may not exist for this man. Not all experiences are universal. Not all experiences are shared. Indeed, the word ‘universal’ emerges in the 14th Century, in Middle English, well after so much Indigenous history.

There is a temptation to fill emptiness and silence with one’s own experience. Indeed, this is how so many abstract stories, presenting quasi-archetypal situations, concretely described, are read. The contemporary reader, she is told, has great authority. She is encouraged to bring her own life to it. Yet the reader and the writer may both be insufficient to depict truth, yet still sufficient for their own myopic needs, and so continues the cycle of generic structures utilised to organise and pre-determine Indigenous representation.

In the scene described, one figure has been neglected: the photographer. It is not a snapshot created by an invisible, pansophical portal. Positioned many metres away from the children, camels, carcass, and man, this individual stood and took this candid photograph without permission. Whoever they were likely did not know this man either. There is no omniscient, god-like judgement, no matter how hard the 19th Century Russian novelist may have tried, no matter how successfully authors continue to try to give such words a veneer of authority. The metafictional construction is always present, is always real(ist).

Instead of a literary voice, in a style popular at the time (if you are from the 1920s, choose Woolf; if you are from the 1950s, choose Hemingway; if you are from the 1970s, choose Carver; if you are from the 1990s, choose McCarthy, etc.), let there simply be silence. And let this silence be respected.

The temptation, when dealing with such self-awareness, is to shift gears into irony. There is an allure to smarmily caption this photograph as if it were a cartoon panel: “A camel is a horse designed by committee.” As a joke, it works. This saying is often attributed to the English-Greek automobile designer, Sir Alexander Arnold Constantine Issignosis/Αλέξανδρος Αρνόλδος Κωνσταντίνος Ισηγόνης. Issignosis is known for the development of the Mini, which was launched by the British Motor Company in 1959. W/r/t the camel, Issignosis’ point was to criticise group decision-making. The individual, Issignosis posited, likely citing Nietzsche, knew what was best for the culture. Yet the camel appears far better suited to the Australian environment than the horse. At least, it does in this photograph involving the man, children, camels, and horse carcass. In the right context, a horse designed by committee (i.e. a camel) seems preferable. Perhaps it is just a matter of the committee having the right input.

Another saying attributed to Issignosis is: “The public don’t know what they want; it’s my job to tell them.” The Mini was released by the British Motor Corporation in 1959. Yet in the environment of the scene described, the Mini would be pointless. Indeed, certain parts of Australia still have terrain inadequate for motorcars. Perhaps, contained in Issignosis’ offering lies the presumption that worlds should adapt to his invention. Or perhaps, he saw the British Motor Corporation as simply a British company, globalisation having not yet fully taken hold of his consciousness. In either case, ‘public’ is not a single entity. One can speak to only so many publics. Try as we might, as businesspeople and authors, to court the polyphonic public, it remains elusive. There are markets Issignosis will never crack. At least, not without sufficient market research. Market research that would be gathered, ideally, by some sort of committee.

For much of 2020, the Australian archives were inaccessible due to the spread of coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). The agony of this inaccessibility is allayed by exploring the digital archive. Pandemics, one quickly learns, are historic. Not uncommon. One is disheartened to find the old scripts, scene and act designs, and machinations being re-played in the present. Lessons not learnt. Or perhaps only now being properly comprehended. The problem with history, it seems, is that there is just so much of it.

And then there is the fiction, which is never about what it appears to be about. Pandemic literature is not about pandemics. Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1353), Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), Edgar Allen Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (1842), Albert Camus’ La Peste (1947) involve pandemics, but they’re not really about pandemics. Just as the deluge of post-2020 literature set in the times of COVID-19 and mass-quarantine will not be about COVID-19 as such. Just as this book, these stories, and these asides are not really about camels.

After the Pandemic

The dust from demolished buildings had not yet settled. Infected individuals had not yet returned from quarantine at North Head. The ghostly tang of lime chloride and burnt rat hair cloaked the city, singeing every nostril. There was no longer peripheral scampering. No rodents in corners or streets. Just the odd tiny skeleton here and there amidst sand massaged by firm, invisible, erosive hands.

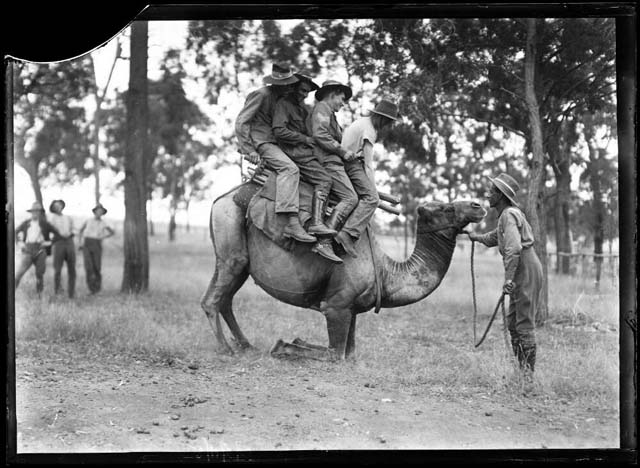

Rusty grunts punctuated the ululating wind. Tied in the mayor’s yard was a once-beloved shaggy camel. It was a quirky trait of the mayor that he had a camel for a pet. It helped establish his persona among the voting public. At events, he would often claim that he was the man with the plan and (after a pause for emphasis) a camel. The animal was an unusually pleasant creature. It would stride towards passers-by and give a grunt. Often it would lower its head over the fence of its pen, allowing children to scratch behind its ears.

Today, no one in the city liked the camel. No one liked anything. There was the frustration of imprecise blame. And this frustration needed an outlet.

A group of six townsfolk had gathered beside the mayor’s house. Stuart Farnell – a pharmacist whose building had been so infested with mice it was deemed impossible to disinfect and therefore burned in accordance with recently passed agricultural protection and health policy – was feeling raw. He had gathered the group. He knocked on the mayor’s door and called out, ‘I’d like a word with you, Mr. Mayor!’ No one answered. In the yard, the camel gave out a cry.

![(1912) ‘“The Snake” Camel [B 24760]’, Kalgoorlie – Port Augusta Railway Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1912) ‘“The Snake” Camel [B 24760]’, Kalgoorlie – Port Augusta Railway Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image19.jpg)

The six men had untended beards, unwashed clothes, unrested eyes, and unexamined lives. One had a bottle of whiskey and was passing it around. They wanted vengeance. They wanted clarity. They wanted blood.

The mayor returned to see the group waiting outside his home. He had been visiting an acquaintance a few houses down. ‘Can I help you, Mr. Farnell?’ said the mayor. It was not a question. It was an aggressive assertion. A plea to disperse.

‘Yes, you can help me,’ said Stuart. ‘You can destroy your camel, which no doubt spreads disease and brings harm to our town.’ Stuart was mimicking the mayor’s own words about mice and rats.

‘There is no science that indicates camels spread plague,’ stated the mayor. His trembling voice indicated he knew that scientific logic would not help deescalate the group’s antipathy.

‘Nah. No one knows where the sickness comes from. Or if it even exists,’ said a man with multiple blowflies buzzing near his ear. ‘Best to make sure, hey.’ The man flicked away the flies with a delicate swish of his palm. He picked up a plank of wood beside the fence, leapt into the mayor’s yard, and bashed the camel in the face. The camel wailed and hissed.

![(1912) ‘“Zabad” Camel [B 24748]’, Kalgoorlie – Port Augusta Railway Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA (1912) ‘“Zabad” Camel [B 24748]’, Kalgoorlie – Port Augusta Railway Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA](img/docmedia/image20.jpg)

More joined him. They passed around the plank of wood and took turns prodding and beating the camel. They passed the plank as they passed the whiskey bottle. It seemed to help them forget the present. They laughed. The camel, they seemed to believe, absorbed their resentment. It was not a youthful animal. It was soon groaning on the ground. Once it could not stand, the men stopped striking. The camel was dead within minutes.

During the beating, the mayor had retreated to his house and locked the door. Stuart Farnell, feeling bold, yelled, ‘You should also burn your house, which no doubt harbours disease and brings harm to our town!’

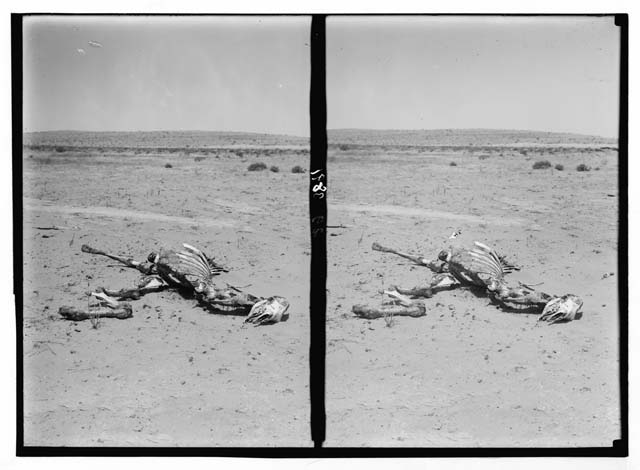

![(1925) ‘Dead camel [B 45085/109]’, Album Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1925) ‘Dead camel [B 45085/109]’, Album Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image21.jpg)

The Chinese word for camel is 骆驼 (luòtuó). The Russian word for camel is верблюд (verblyud). The Japanese word for camel is駱駝 (rakuda). The Armenian word for camel is Ուղտ (ught).

Despite the malleability and evolutionary capabilities of the English language, there remain archival oceans that are inaccessible for English speakers and readers. Try as we might, many of us will never learn the language(s) necessary to gain access to knowledge. The total is unknowable.

In such dire, info-saturated circumstances, one is tempted to rely on a few precise impressions. These become navigational tools. Contemporary understanding is not a matter of discovery, but orientation. We need some way of determining our position: an anchor, a true north, a constant. In this case, it is the camel.

Some of us rely only on vague feelings and bad presumptions. History and the contemporary are littered with ill foundations. This either leads to self-destruction or total transformation: the realisation that nothing in life has been true, that there is no anchor, no true north, no constant. At such moments, the personality dissolves: that which we think we are – our character – ceases to be. During such confrontations, the fiction writers argue, we experience catharsis, or judgement, or ‘development’. But when there are no actual endings (excluding death) coupled with the realisation that such realisations could further be turned once more, one questions one’s own authenticity. There is nothing to hold onto.

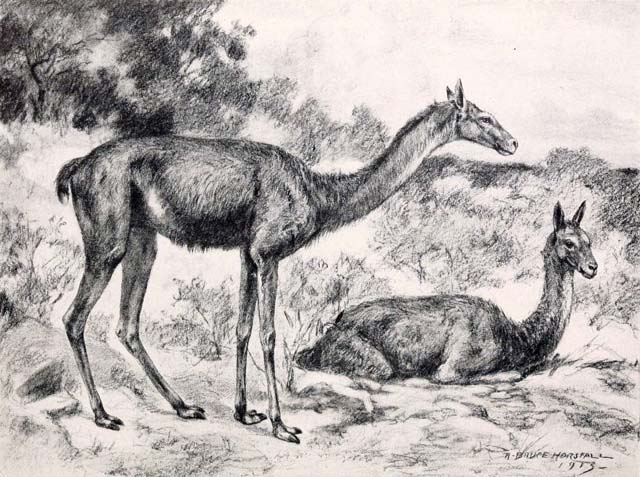

For now, the camel remains relatively constant. There are only a few members of the Camelidae family. Though history has variations such as the Oxydactylus, which lived from the Late Oligocene to the Middle Miocene. One wonders how many additional variations of the camel remain buried around the world, fossils and bones washed away by time, never to be found or imagined.

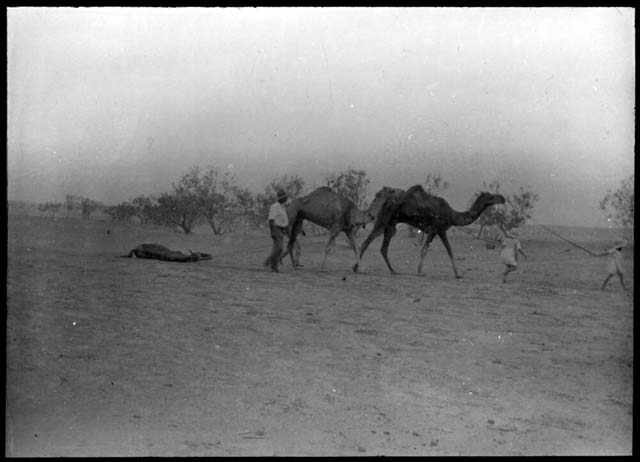

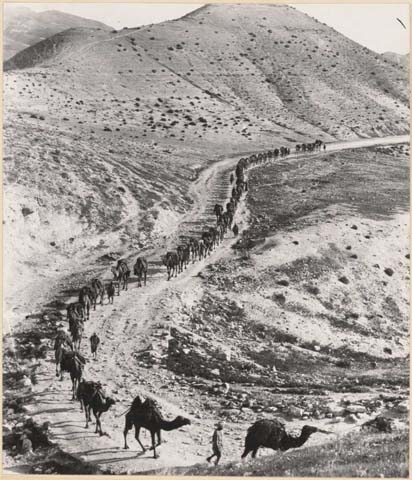

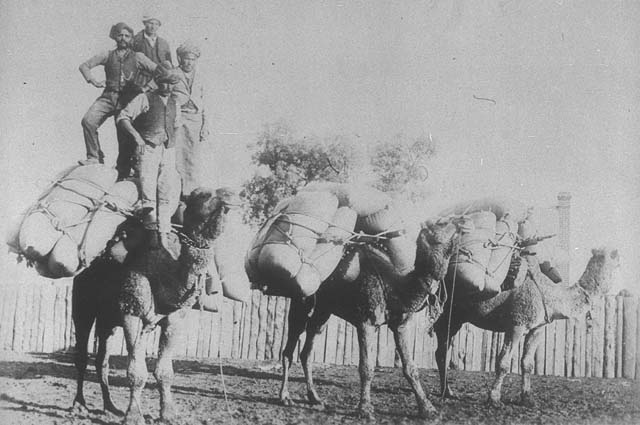

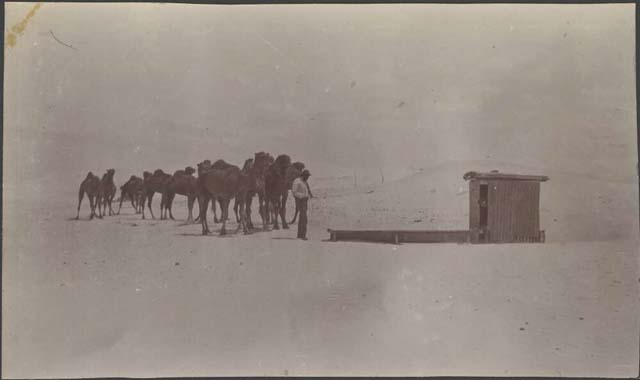

The Manure Coolie

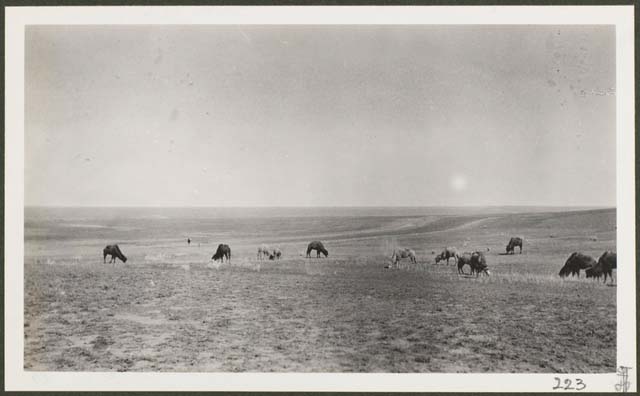

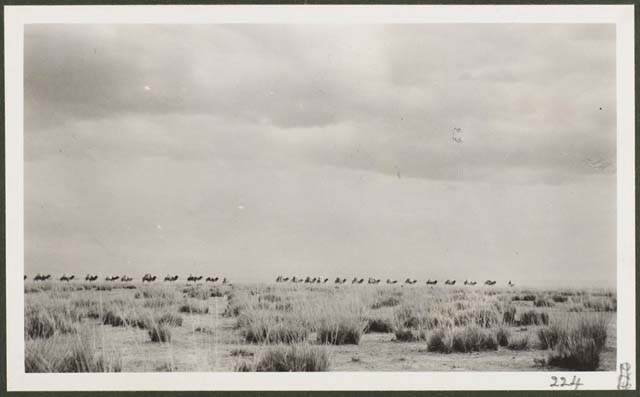

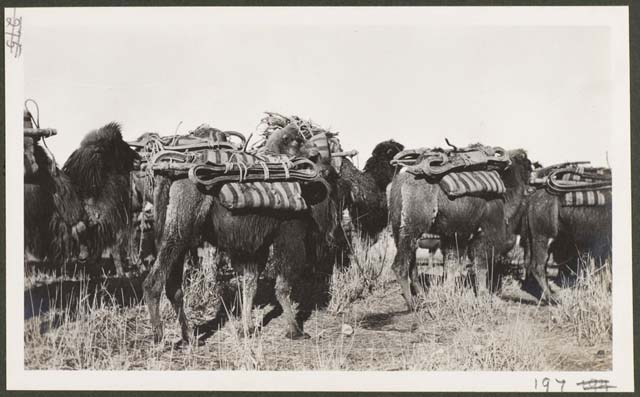

As George Ernest Morrison looked out at the camels grazing on the horizon, he thought he was in Australia. He was experiencing what the French, a few years ago, had started calling déjà vu: already seen. Morrison, however, was not yet aware of this term or phenomenon, and so was quite unsettled. In fact, his entire orientation on the planet, in the universe, was thrown into question. This journey, one of many he had taken on the Eurasian continent, was from Burma to Russian Turkestan. There were many Chinese scattered about, but Morrison was not certain that this was China, as such. As the saddle chafed his thighs, as the sun glared, Morrison was even beginning to question what hemisphere he was on. The sun, at least, Morrison was sure, was consistent.

These camels were not the same as those in Australia. They were woollier. They had two humps, that varied in size and shape, like bizarre appendages, added on at the last minute by some perverse God.

A torrid wind blasted the stench of camel manure. The scent was near-identical to that produced by Australian camels. This resulted in a phenomenon called ‘involuntary memory’, which Marcel Proust, a few years later, would coin in his À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. Many years later, neuroscientists would research the piriform cortex, a part of the olfactory brain, and its relation to the storing of long-term memory. Morrison, in 1910, however, was unaware of such processes, and was therefore terrified by this conjuring of camels past. Everything seemed familiar, yet potently unfamiliar. He lacked the words to describe what he was feeling. Unlike Proust, Morrison was not a great writer. He lived off and adored words (his memoir of traveling across China had granted him his current correspondent position with The Times), but he knew he lacked precision. Gut feelings were never authentically transferred to the page. He felt his writing too political. Not the politics of folks in top hats federating states. Not the politics of Tafts, Bartons, or Bannermans, but the pragmatism of one hoping to preserve… what? Morrison’s writing lacked… He lacked… In a previous life he had strolled the route that killed Bourke and Wills and wrote that it was a ‘pleasant excursion’. His writing flattered. Himself, his needs. Smoothed reality’s edges. He was fraudulent and he knew it. Yet even now, as the straw-like scent of camel manure flared his nostrils, he could barely articulate his own dishonesty. Any attempt at eloquence produced only a nonsensical gurgle, which, perhaps was the way language was going.☨

The camels, Morrison saw, were being packed with hoop iron. Almost a century before its economy would become the largest in the world with a GDP (PPP) of $25.7 trillion, the mechanisation of China was kicking into gear. Something was happening in these lands. Civil stirrings. Seismic political activity. Yet he had no idea what he was to tell the editors back in London of the current state of this part of the world. He had plenty of time to think about it. After his arrival in Andijan, he planned to travel on to St Petersburg via train. Yet time would not help. Years in these parts had made the Chinese languages and meanings no less impenetrable. He would never know the Chinese people intimately, would never understand the clockwork of their minds or society. As the Chinese camels stood and plodded off with their load, in the opposite direction to his convoy, he acknowledged just how little he knew, how little insight he had. His ignorance, Morrison conceded, was vast. In his travels, he had collected books on China, yet could not read a single page. Earlier that day, as he had lifted his luggage onto his horse’s back, those books had felt particularly heavy. Everything now seemed so Oriental. Not just the Orient. Everywhere, everyone was orientalising. Sense, Morrison thought, was slipping through our fingers, whoever, ‘our’, ‘us’, ‘we’ is. Perhaps that’s just it. Perhaps it’s just ‘it’.

Perhaps he was simply dehydrated. Before long, Morrison reassured himself, they would be approaching a town, where he could eat and be ogled by locals. One last whiff of camel dung floated to Morrison’s nose, and he was reminded not of Australian camels, but of his passing through Pupiao, not far from the plain of Yungchang. The entire town had flocked to see pale-skinned Morrison eat his lunch. Following his meal, he had jokingly bowed to the crowd, and in pristine English, mentioned that they would contribute to the comfort of future travellers, if only they would pay a little more attention to their table manners. Then, addressing the innkeeper, Morrison thought it only right to point out that it was absurd to expect that one small black cloth should wipe all cups and cup-lids, all tables, all spilt tea, and all dishes, all through the day, without getting dirty. Morrison had pointed out another defect of management to the innkeeper, telling him, again in plain English, that, while Morrison personally had an open mind on the subject, other travellers might come his way who would disapprove of the manure coolie passing through the restaurant with his buckets at mealtime, and halting by the table to see the stranger eat.☨ That moment in Pupiao, Morrison realised, was linked to this whiff of camel faeces. The manure the coolie had carried must have been from a camel. Morrison again pictured the coolie’s stare. His brown irises. The unblinking eyes. Perhaps the coolie’s stare had not been one of curiosity at all.

⁂

That evening, in a hard, straw bed in a dilapidated inn, Morrison thought once more of the manure coolie. He believed no person was crueller than the Chinese. Their sensory nervous system was blunted. He had written extensively on the subject:

Can anyone doubt this who witnesses the stoicism with which a Chinaman can endure physical pain when sustaining surgical operation without chloroform, the comfort with which he can thrive amid foul and penetrating smells, the calmness with which he can sleep amid the noise of gunfire and crackers, drums and tomtoms, and the indifference with which he contemplates the sufferings of lower animals, and the infliction of tortures on higher? ☨

Morrison, in a dreamy state, wondered if the same was true of Chinese camels. Could they carry more or less iron?

![(1911) ‘Camel Train [B 9788]’, General Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1911) ‘Camel Train [B 9788]’, General Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image28.jpg)

Perhaps he was wrong about the Chinese. Perhaps if they were a crueller people, they would succeed in claiming the world. What a peculiar, unimaginable future that would be, thought Morrison, where all the words were squiggles, where all meaning floated in the air in singsong tones among the sweet scent of camel dung, where beasts had not one but two protuberances, where manure coolies stared as they ate our food…

William Strutt’s ‘Black Thursday, February 6th. 1851’ depicts the Black Thursday bushfires. It is an oil painting on canvas, produced in 1864, thirteen years after the incident. In his journal, Strutt wrote:

The sun looked red all day, almost as blood, and the sky the colour of mahogany. We felt in town that something terrible (with the immense volumes of smoke) must be going on up country and sure enough messenger after messenger came flocking in with tales of distress and horror.

Viewing this painting, I often search for a camel. I feel there should be one. Perhaps some of the bones are from a camel’s skeleton. Or in the far right, among the smoky silhouettes of kangaroos there is a camel tail or neck. ‘Black Thursday, February 6th. 1851’ is an emblematic work of an Australian tragedy. And the camel was not and has never been an Australian emblem. Perhaps it is off-canvas. At water. Perhaps it is savvier, more capable of survival than these beasts. Than these people. If the camel is absent, its absence is meaningful.

Demon Steed

The seeds of the banksia are fire-activated. Only in the wake of inferno do their seeds release, ensuring that they germinate on cleared land. So, it seems, did my consciousness germinate. Fire is my earliest recollection. In tracing my palimpsest of memories, my awareness appears to have literally been ignited. Shades of orange, yellow, red. And prickling heat. Ineluctable heat. I recall being able to see and feel the colours even when I closed my eyes. As a child I thought the fire was in my head, as though a cinder had gotten caught behind my eyeball and was lighting my mind up like a jack-o-lantern. A permanent, inerasable phosphene. Rubbing my eyes made it worse, made it brighter. Sharpened the sting. Vision had been hijacked, painted terrifying colours. I began to cry. The tears did not allay the heat or hurt. Moisture melded with ash. Great flecks of soot lowered from the sky. Ruby embers bit like callous mosquitoes. I felt unclean. My face was charcoal. I saw only black and orange. The blues and greens, I thought, had been removed. Eliminated from this world.

They named it Black Sunday, which always made sense to me. Decades later, in the ‘70s, when we first saw the image of Earth from space – The Blue Marble – it wasn’t as I imagined it. The blue and green and white and ochre. I thought the world black and orange.

When we escaped the fire and arrived at a small clearing with a shallow creek, we spotted a camel lapping. It was haggard and burned. Its face and sides were blistered. There was the acridity of burnt hair. I can still smell it. My father tried to shoo the camel away, but it refused to budge. Its indifference and resignation seemed cruel. If the animal had any respect, I thought, it would have had the decency to die. In my infantile mind, I equated the horror of the bushfire with this horribly disfigured animal. I considered it a demon. Responsible for suffering.

In the nights that followed I was possessed by red and orange nightmares of blistered, moaning camels. Sometimes I woke and started sobbing. Sometimes I shrieked myself awake. I always woke my parents. They allowed me to sleep with them.

After months and comments from my mother that ‘big girls should sleep in their own beds’, I still experienced night terrors.

As I grew older, the nightmares subsided, but never fully went away. I recall when I was seven, my mother took me to Melbourne to see the circus. We didn’t see the actual performance, just poked our noses in at the animals in their cages. I delighted at the laziness of the sleeping seals and the impatience of the pacing lions. Then we saw the camels and I started to cry.

The same thing happened that same year at my birthday. My mother brought out a cake with seven candles on it, and she started singing in German. I started bawling at the sight of tiny flames. Over the years there were dozens of involuntary prompts like this. Usually attributed to camels or fire, but not always. Once, just the glare of the sun set me off. My parents were rural, hard people. They weren’t fond of sensitivity. Believed I was precious. I heard my father mutter to my mother, ‘Flo’d never make it on her own.’ Oddly enough, that did not make me cry. I just felt sorry for my father.

He used to work on a vineyard. We were not poor, but in those days everyone felt poor. Our family are a distant relation to Dame Nellie Melba, whose father or grandfather (I don’t recall; I’ve never met the woman) had planted acres of vines with a view to making wine. This would have been a shrewd move, were it not for the fire. It wiped out everything. Green was made black and brown. The Depression made everyone switch back to pastures. In those days, there was no need for fine wine. There was nothing pleasant happening, no reason to toast. Alcohol was consumed only by the miserable, and they were not picky or rich. Preferred their grog sticky and brown.

Around this time I had a bit of a breakdown. It’s hard to say if I was actually troubled or just being moody. I stayed in my room and refused to come out of my bed for days. Refused to go to school. I read Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. My father had introduced me to the latter. He claimed to have shared a drink with Twain at the Melbourne Cup many years ago. I think my father was lying. My father told a lot of lies, but they were always nice lies. The kind of lie that made me wish for more excitement. To run away from this place. I was what the Americans had begun to call a ‘teenager’. My father thought I was being self-centred. Perhaps he was right. It was a stressful time for everyone. As such, it was unbecoming to complain. If you did not serve in the war and you could get by, you were obliged to keep your complaints to a minimum. So I offered to feed the cows. My father had brought Brahman cattle from a destitute farmer in Queensland. According to him, the farmer was an alcoholic.

The breed, like Mark Twain, was from the United States. I found them most peculiar. I’d never seen anything quite like it. I thought them camels because they shared a fatty hump. Yet I was not afraid of them.

‘Zebus,’ my father called them. ‘They’ll like it here. Not afraid of a bit of heat.’ I smiled at my father’s joke, but did not enjoy it. I found it impossible to treat fire and heat as a source of anything but grave seriousness.

I enjoyed watching the cows. They are friendly animals. Often the Brahmans would approach and relish being scratched on their chubby, thick necks. After that I had trouble eating beef, even stew, but to even hint at reluctance towards meat would have been an insult to my father’s profession and hard work; to turn down any food in the Depression was blasphemous.

As I grew into adulthood, I opted to study German. I had picked up enough from my mother’s muttering. She liked speaking German. Missed making conversation in her mother tongue. Occasionally, my father would try to converse with her. He told me that he spoke fluent German, but it was obvious that his vocabulary was extremely limited. As I said, my father told a lot of sweet lies. He would say things like, ‘Was für ein schöner Tag, was für eine schöne Frau.’ He called me Florenz, rather than Florence. He would always emphasise the z, and turn it into a snake’s hiss or a bee’s buzz, accompanied with swirling arm or darting hand, depending on which animal he chose. My father was a cosmopolitan man. Had a lot of respect for Edward William Cole. Admired his zany behaviour. His arcade full of books, his monkeys and marmosets, his outrageously public approach to romance. ‘He put an advertisement in the newspaper, claiming he wanted a wife. I’m not joking! I read it in the broadsheets!’ I think that was another of my father’s fibs.

He was supportive of me learning German. My father hated the assimilationist attitudes of the country. ‘Anyone who thinks we can be English-speaking forever is kidding themselves,’ he would emphasise. ‘We’re in the Orient! And England is far, far away…’ He hated things passionately. He hated the nationalist poetry of Mary Gilmore. Called her a communist. But he liked Banjo Paterson. I always found him a bit twee, but never said so to my father, who loved to quote long stretches of Saltbush Bill, J.P. from memory whenever my mother made strudel.

Grass and green returned. I headed into the city to study and work.

Then fire broke out again. As it tends to do. This time on a Friday. Black Friday they called it. They were not exactly creative with the names.

Then war broke out again. As it tends to do. Not sure what day specifically. They soon started calling it World War II. Again, whoever labelled such things was not very creative with the names.

⁂

I found myself surrounded by grey. No greens. No blues. Not even orange. I was in Munich. München. At the Bavarian State Library. The Landesbibliothek. Well after Hitler and all that followed. The country was now split in two. But after a lifetime of messiness with the Europeans and their fighting and politics, I did not have the energy to invest myself too deeply in the day-to-day political goings-on. Or perhaps I feared what would become of them, what I would learn and believe if I scratched the contemporary surface too deeply. There was no doubt about it: things were still strange. Strange in ways that the general foreignness of Europe could not equate for. I had heard the stories of Nazis burning books. In Berlin, on what is now called The Bebelplatz. The pages of Mann, Remarque, Heine, Marx, Einstein… all up in smoke. The words still whisper in the air. The incomprehensible suffering. Too much. Too much to comprehend. Best to stick to the old, old past, the old, old tomes. While they were still here, available, readable, touchable… Ignore the immediate past, the immediate present and focus on…

I am here researching German Literature. I have recently been added to the faculty of the University of Melbourne, following their amalgamation with the Melbourne Teachers’ College. I teach and research European Literature. I also dabble in history and language. Often I am required (read, forced) to teach education. I can speak French, Spanish, Italian, German, and a splash of Dutch. I have also published a book on Dante: Dante’s Demonology (1972). This was accepted and distributed under the pen-name F.P. Cartwright. In submitting my manuscript for publication, I recalled Miles Franklin’s letter to Henry Lawson. The latter claimed he knew it was a woman writing. I wonder if the same was true of my publishers.

Previously I taught all-female classes. The recent conjoining of the faculties has the men at the university irritated. My publications and fluencies are far from respected. This is why I’ve taken it upon myself to acquire the funds to get away to gloomy Germany. As with my manuscript submission, I was sure to complete the grant application using the initials F.P., rather than my full name (Florence Penelope Cartwright) for fear of receiving the same treatment by the Australian-European Exchange Grant committee.

I am interested in old European myths and mysticism. The grimoires. Zauberbücher. I have been perusing the library for days now. Amongst the grey sky and landscape; the mushroom smell of old pages; the cold yet agreeable indifference of the librarians and fellow researchers; the comforting routine of the two sausages and sauerkraut, accompanied with a small beer, for dinner; the menial clockwork of my research plan slowly amassing a book of notations; and the apathetic acceptance of my no-doubt ocker-accented German. All of this seemed pleasant enough in a place that had seen so much recent chaos. Despite the hardness of my motel mattress, the intermittent clunking of the ancient pipes, and the chill of the night, I have never slept so soundly.

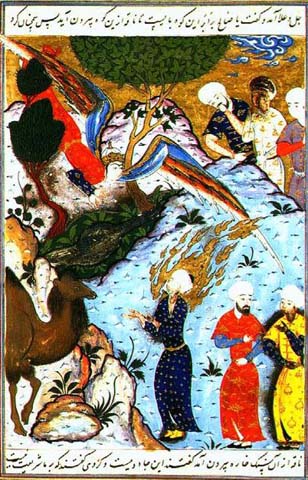

That was, until I came across Louis Le Breton’s illustrations for the 1863 edition of Dictionnaire Infernal: ou Répertoire universal des êtres, des personnages by Jacques Auguste Simon Collin de Plancy. And all at once I saw black and orange. Despite the frosty weather, I felt hot. I started huffing. I felt the other researchers’ stares upon me. The sausage and sauerkraut in my stomach churned. Acidity rose. I felt oesophageal burning. Burning. I tried to continue reading the dictionary entry:

…puissant duc des enfers; il apparaît sous la forme d’une femme; il a une couronne ducale sur ta tête, et il est monté sur un chameau. Il répond sur le present, le passé et l’avenir; il fait découvrir les trésors caches; il commande à vingt-six legions. (307)

Which translates roughly to:

…mighty duke of the underworld; he appears in the form of a woman; he has a ducal crown on his head, and rides a camel. He responds to the present, past, and future; he reveals hidden treasures; he commands twenty-six legions.

Without packing up my things, I rose and rushed down two floors to the lavatory and hid in the cubicle. The toilet seat was like ice. I expelled liquid faeces in a diarrheal burst.

Despite light-headedness, I suddenly felt a great clarity. My fears, what my father had called my sensitivity, seemed justified. Appropriate. These demons were necessary symbols for uncontrollable horrors… a fun spooky indulgence… a gothic sublime… just a silly parodic reference book for French readers in the 19th Century… no longer possible. No longer moral.

My experiences as a child, as scarring and devastating as they were, minimal in contrast to… nature? Human or non-human? Either way, cruel and indifferent… we were, are, will continue to be… unable to comprehend the sheer numbers and size and scope… we are just nature, and yet not… another watery bowel movement, additional dizziness… beer a mistake… all of it, a mistake… I am done with Dante Alighieri, whose hells seem charming in contrast to… here, now… here, moments ago… only a few years, a few miles. How do they go about their business? How do they continue to serve sausage and beer and read their books? Do they not just see orange and black? Or am I just being overly sensitive, as my father used to say? Black and orange made sense. The only sense. The only clarity or answer or explanation…

I cleaned up. Left the bathroom. Returned my books. Returned to my motel. Failed to sleep. As Australians ate Brahman steaks. As Germans sold beer. As microscopic flecks of burned books and materials (materials?) continued to float around me.

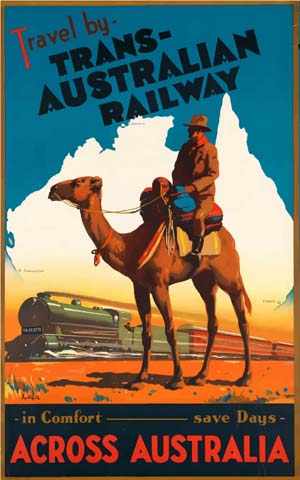

For many years, Australians have had camels in their pockets. If you look carefully at the previous polymer $20 note, with its compass-framed transparent window, on the side with Reverend John Flynn’s face you will note a de Havilland DH.50 biplane, an image of the pedal wireless invented by Alfred Hermann Traeger, and, to the right of Flynn, a man atop a camel. This is a ‘Patrol Padre’. Missionaries on camels were one of the earliest attempts at providing suitable healthcare to the residents of inland Australia.

The latest design of the polymer $20 note, released in October 2019, has no camel. As older forms of currency disappear, replaced by sleeker designs with better features to ward off counterfeiters, the barely-noticed camel beside Flynn’s neck will soon disappear from Australian pockets. Indeed, tapping plastic credit cards on devices to process contactless payments will soon dissolve our need for cash altogether. All payments will be made over cellular networks or ethernet connections, Wi-Fi, or standard telephone lines.

These communications are possible largely thanks to the Australian Overland Telegraph Line, completed in 1872, which introduced fast communication between Australia and the rest of the world. Before the Telegraph Line was in place, messages were delivered across these incommunicable sections by camels. This great engineering feat of the nineteenth century also depended largely on camels.

![(1896) ‘P.S. Nile and barge approaching Wilcannia Bridge with camels crossing overhead [PRG 1258/1/2875]’, Godson Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1896) ‘P.S. Nile and barge approaching Wilcannia Bridge with camels crossing overhead [PRG 1258/1/2875]’, Godson Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image35.jpg)

There is no escaping the camel. Like cash, it is an invisible force that determines everything. It is a fiction. It is a physicality. It is a non-human potency. The country depends on it. Is shamefaced without it. Is ashamed of our dependency on it.

Retirement of the Species

Its lashes were long and feminine; its bizarre lips an anthropomorphised sneer, as if chuckling at a caustic joke. This is the personality the woman attributed to this camel, to all camels, which she regarded as the most stubborn and self-serving of beasts. She imagined the local camel as she scrubbed her children’s clothes on the washboard, thrusting the garments with such force she almost sprained her wrists. The astringent scent of laundry soap further soured her dusk mood.

Her late husband, a stockman, had been crushed by a cow’s hoof; his pelvic bone had shattered. The ultimate cause of death, she had been informed, was a ruptured bladder. She disagreed with this assessment. There was no doubt in her mind that her husband’s cause of death was the lethargy of camels. A Patrol Padre had attempted to transport her husband on camelback to receive adequate treatment at a nearby outpost. The self-serving camel, she suspected, had not cooperated. She had witnessed their slothful, unhelpful attitude time and time again. She knew in her heart and soul that her husband’s camel escort had sat on the ground. Had refused to move. Had been indifferent towards his suffering. Her husband died before he got halfway to his destination. The camel needed to take responsibility.

This perverse fantasy was now her escape, her entire landscape.

News of her husband’s death had been slow to arrive. Her husband had been dead for two months before she found out. The news had arrived on camelback. Unlike, this morning’s news. Word now spread via radio: the town had just been informed of the first successful flight performed by the AIM Aerial Medical Service. This, the woman had been reassured, was the way of the future. With flights and transmissions, with winds and waves, the continent had been conquered. The furthest corner could and would be reached. Aircraft and radio would fix everything. Camels were no longer required, could be retired. This perspective, provided by wives of healthy stockmen, was meant to make her feel better. To mollify her. Neighbouring women invited her to envision a country buzzing with aircraft, swarming skies like so many horseflies. She was encouraged to imagine all information available and understood by all at all times: a collective human consciousness. These idealistic, gossipy women insisted that she indulge notions of a utopic culture where all injury and illness was curable and cured, where all needs and desires could and would be met and augmented. Her neighbours, she suspected, were sick of waiting: they needed her to cheer up and stop moping. One particularly irritating stickybeak, an Irish lady named Roisin Byrne, had been less than subtle, ‘Your man’s dead. Time to get on with it.’

Despite this promised security, she remained unable to sleep. One night, she decided to ‘get on with it’. She abandoned her three-room house and the delicate snores of her three boys to pay a visit to the local camel. She stomped through the dark, tired town, determined. When she reached the paddock, it was grunting, or perhaps snoring. The creature’s idleness was an insult. The woman picked up a stick and prodded the animal’s eye through the fence. Its thick lashes opened before it let out a quiet moan, which produced mist in the evening air. The days here were hot, the nights frosty. The worst of both worlds, thought the woman. A warm wind spurred shivers and goosebumps. The camel raised its muscular, elongated neck, cobra-like.

The woman recalled her neighbours’ jest that the camel could be retired. Without humour, she agreed. She lifted the latch of the paddock gate and stepped inside, her cautious footsteps crunching dry grass, producing delicate crepitations. The camel’s ears fluttered. It remained on the ground. As its species did while her husband lay dying. The woman felt a violent lust, a desire to kick the animal, to strangle its perverse neck. She was trembling.

She had no desire to return home. Like the camel she wished to relinquish, she wanted to wander out into the desert. Her life appeared entirely dependent on the kindness of townsfolk, which was already waning. Offers of meals and hugs had become less frequent. Would soon be non-existent. There would be a sympathy drought. The woman considered jumping atop the camel and whipping it, forcing it to take her to another town, colony, life…

‘Shoo, shoo!’ she hissed. The woman began clicking her tongue. The camel, on lackadaisical limbs, rose and ambled out of the paddock. With alert curiosity, it strode towards the town.

But it did not leave. Rather, it moved, through the dark, to the woman’s house. It moved quickly, with purpose. The woman’s kitchen had an open window and no floor. The camel inserted its head into the woman’s house in search of food. There was a clash of pots being knocked over. The woman rushed towards it, her feet scraping over dry ground. She slapped the indifferent beast’s hide, grunting, frothing, but the camel refused to eject its head. The woman went into her home and retrieved her washboard, which she used to smack the camel’s head. ‘Get out! Get out!’ The washboard broke. The camel squealed, but remained.

The woman then calmed. There was a peculiar stillness. The camel simply looked at her, as if waiting to be fed. In the other room, subtle snores could still be heard. Unlike her, the woman’s children were deep sleepers. There was some stew in the pot, left over from dinner. Her children had not been eating. Or perhaps were being fed by neighbours who viewed her cooking as inadequate. The woman fetched firewood, put it in the stove. Those same neighbours had told her that she should try to get a gas stove, that gas – like flying machines and magical radio voices – was the way of the future. But as the stove fire started flickering, as the leftover stew started bubbling, as the camel’s snort-like breaths heaved, she realised there was no future. Not for her. There was only this moment. Her and this camel. Extending indefinitely. As the bubbling of stew became violent. With a rag, the woman grabbed the scorching pot handle and tossed the boiling slop at the camel’s head. The camel snapped its head out of the window and roared; the sound bounced into homes, echoing across the landscape, waking the whole colony, and perhaps others as well.

The woman sprinted outside and pounded her fists on the animal, still roaring. Both creatures were inconsolable. The woman’s children had woken up and, upon seeing their frenzied mother, became similarly inconsolable. Even when the neighbours came and tried to calm her, telling her, ‘You’re going to hurt yourself,’ the woman refused to stop shrieking until they had guided the camel out of her sight.

Roisin Byrne, the Irish stickybeak, tended to the woman’s children, calmed their crying and put them back into their beds. She then did the same with the woman. ‘You’ve got to stop this, pet,’ said Roisin, stroking the woman’s hair. ‘You’ve got to stop. You can’t keep wakin’ the whole town every night.’ In the distance, the camel’s roars could still be heard. The animal sounded as though it were in great pain, which brought a wicked smile to the woman’s lips. She fell asleep fantasising of fleets of aircraft equipped with artillery, firing down upon thousands of camels, broadcast to the collective consciousness of the Commonwealth of Australia.

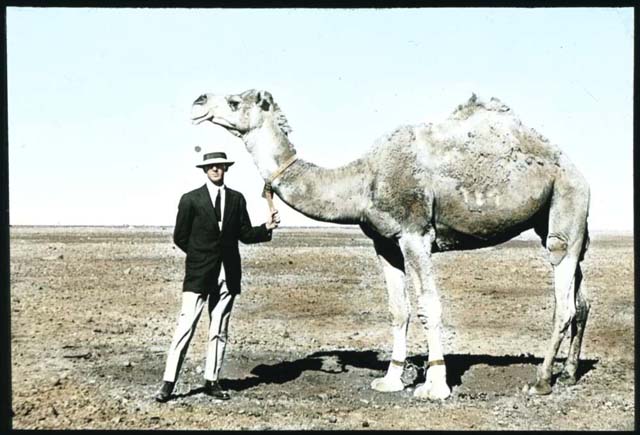

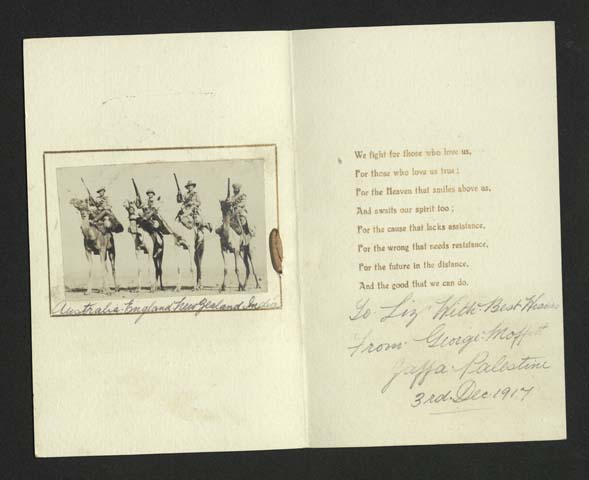

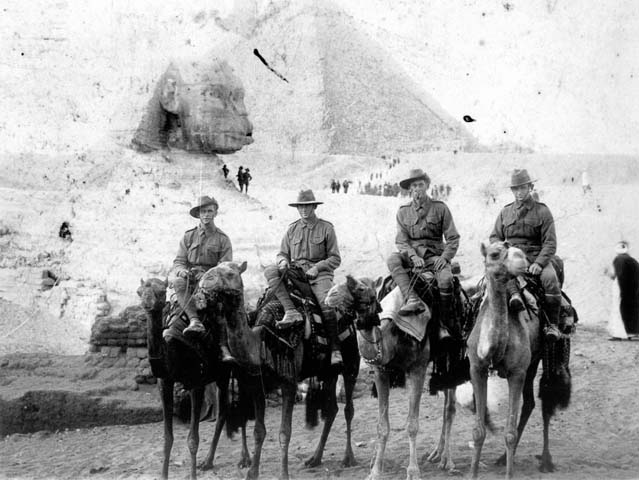

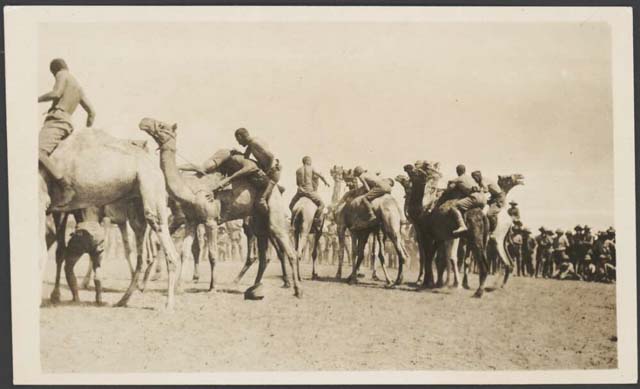

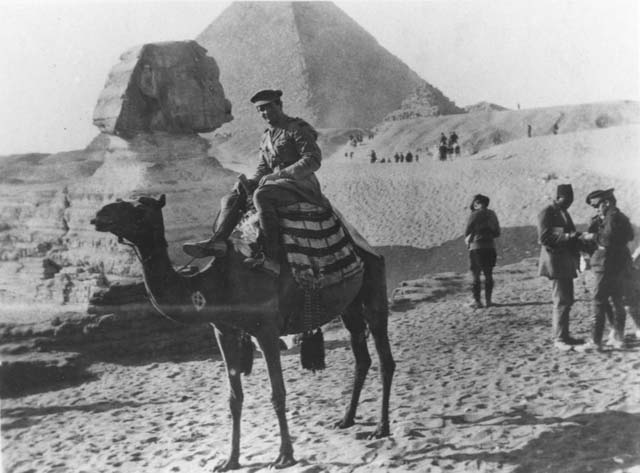

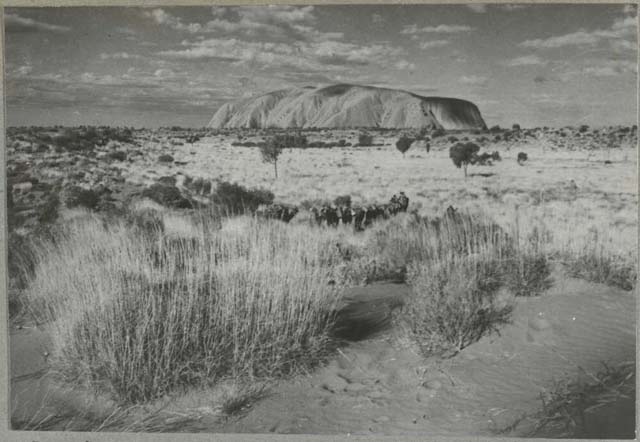

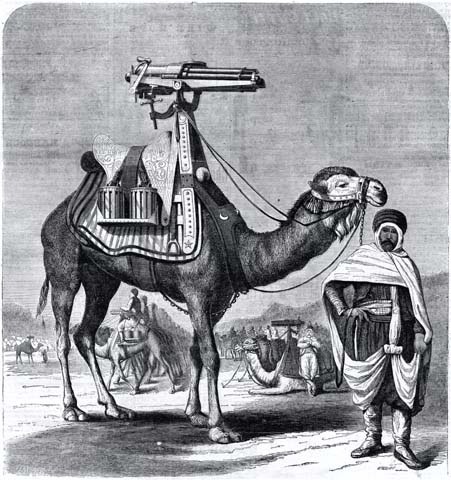

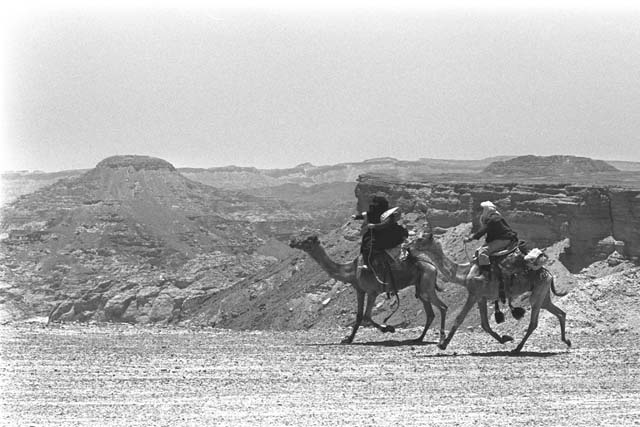

When one thinks of ANZACs and the Gallipoli campaign, one thinks of trenches and machine-gunners and solemnity and remembrance. Yet the images that emerge when one takes a shovel to the archive are largely from training (and indeed, downtime) in Egypt, beside the pyramids. Often the ANZACs are atop camels.

The Gallipoli campaign is often cited as the beginning of Australian and New Zealand’s national consciousness. Before the significance of so much death, there was a brief, fleeting moment when young men arrived in foreign lands with bizarre pyramids on the horizon, moving on beasts that were more comfortable than they were. The cultural shock cannot be reproduced in our interconnected world. These moments may not have had anywhere near the impact of the tragic fate of the Gallipoli campaign. But it did have impact.

The Camel’s Gait

Mate. A partner in marriage. A spouse. One of a pair of mated animals. Counterpart. Fellow. Friend. Pal. To join. Match. Marry. Fit. Connect. Link. Treat as comparable. Copulate. For the purpose of breeding. Consort. I first heard the word…

Gunfire like rain.

“…because of the machine guns, we need some mates to help dig the trenches.”

Mostly men from Ballarat, products of the Eureka Stockade Rebellion.

You’ll be on the front line.

Wasn’t to be. Shrapnel shard to the chest.

Probably saved my life.

What life?

War then…

Don’t have it in me to relive the war.

It’s the other memories…

Absence of memories.

…that ache. War is merely the axle for everything else. War is boring. Tedious. Full of errors and bad judgements. Bureaucratic. Dusty. Unclean. Itchy. Discomforting. Bad smells. But the other recollections…

Other discomforts.

…are…

I go along to the parades and the ceremonies. Put on my gear. It’s expected. I worry I don’t recall or remember things as well as I should.

Don’t weep, don’t care to recall.

1982. ANZAC Day.

One among so many.

Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance.

I was there.

‘Stop those men!’

Cries. Not peaceful. Not silent.

Respectful?

I guess it depends on who you’re talking to.

Didn’t follow up the story. Didn’t think much of it at the time.

Didn’t think he should’ve called them poofters. Didn’t think they were denigrating anything.

To disagree is why you fight in the first place. But what do I know? I just show up and do my job.

Then what?

It was Ruxton causing the fuss.

Bruce Carlyle Ruxton. AM, OBE. Always carrying on and spouting some line or getting in some fight.

Never had a major problem with the guy. But I never liked to complain about those in charge. Did my job.

And then what?

Mind kicks over, falls into subconscious cravings.

After the war there was no mateship.

Ruxton saw to that.

But one man isn’t everything. You can’t just…

Never was.

For others, yes.

Ruxton was wrong on that, saying he didn’t remember a single one…

HOMOSEXUAL BEHAVIOUR IN

THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE

Bunked with bunches of blokes and then a long, extended solitary…

Homosexual behaviour is not accepted or condoned in the Defence Force. Defence policy…

There’s the rules and then there’s the reality.

…makes adequate provision for the discharge of members who engage in homosexual activities where factors such as…

Loneliness?

Keep busy. Keep your boots clean. Wear a suit. Go to church.

Head down.

People must assume…

Are they right?

I don’t know…

Perhaps they assume I’m too ugly. Not a good looking…

A face to make babies cry. Involuntarily.

I don’t cry. Never got upset about it, which is probably why…

Wouldn’t know.

Know to stay away.

Self-pity is for…

I am not passionate. Not tragic. Incapable of…

And yet, the strut of the camel…

Not strange. Correct.

The bizarre expanse of sand. The shapes. Triangles. The beast with its snorts and huffs and confidence…

The queer lion statue. Queer is the right word for it. Lion body, human head. Imposing.

To be that queer and imposing…

Was jealous.

Am.

Too late now.

Could have.

Never even had the imagination to envision…

Whoever imagined the sphinx… the creature and the statue and the…

Will. It’s all about will.

Now.

Then.

The present.

Fantasise. Weird dreams forgotten on waking.

No stranger than a sphinx in ancient Egypt.

A sphinx now.

Dream and nightmare. Both.

Too old.

The unintimate.

There was an erasure.

Tears plugged.

Erosion.

Like the sphinx paws.

They remain.

Now.

To cry is…

Absurd.

Like a sphinx.

Normal to the locals.

Not local.

Foreign.

Foreign there.

Here.

Cannot be done.

Here.

Cannot be tragic.

Now.

Comic.

Like the camel.

Absurd. Look at its hump. This queer horse.

Queer.

Words thrown around.

Comfortable. Irritable, but confident in its irritation.

Like Stonewall Riots. Gay German literature. Certain Sydney bath houses.

You kept your eye on things.

Still…

The epidemic. The bristle of the neck when you overheard ‘they got what they deserved.’

Was there mateship with these folks with their virus?

Is horrible, from what I’ve heard.

They could not resist.

I resisted.

Everything. No assertions. No…

Opportunity. War was the defining…

It’s sad that’s the case. All that…

What was it for exactly? If not this, then…

All.

A discomforted life.

I had seen two soldiers. Young lads…

The camel moving across the sand.

…embracing.

It was romantic. Not just…

I’d never seen it before. It sticks out with great clarity. I wanted the same…

Wanted.

No longer?

Not even a question.

Weird shapes and smells.

Wanting.

They were bold.

Probably stupid.

Sphinx-like. Camel-like.

Queer.

As opposed to…

Pleasant?

The queerness of the landscape, the world…

Felt right.

The camel saw it as normal.

As did I.

Did you?

Only then. Briefly.

Fleetingly. As sand on the wind.

As a giant sphinx overlooked the whole mad event.

War.

Life.

Never again.

Never forget.

Try as we might.

That ride, rhythm, smell…

The only fantasy left.

Holy texts are riddled with camel references. They are found in the Torah, Bible, and Quran. For example:

Then said Jesus unto his disciples, Verily I say unto you, That a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven.

And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of the needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

-Matthew 19:23–24

It is believed that camels were first domesticated around 3,000 BCE.

Excavations in the Timna Valley suggest that camels were not domesticated in Israel until 930 BC, and that the camels in the Bible and Torah are therefore anachronistic, that the stories of Abraham, Jacob, and Joseph were likely conceived centuries after the events supposedly took place.

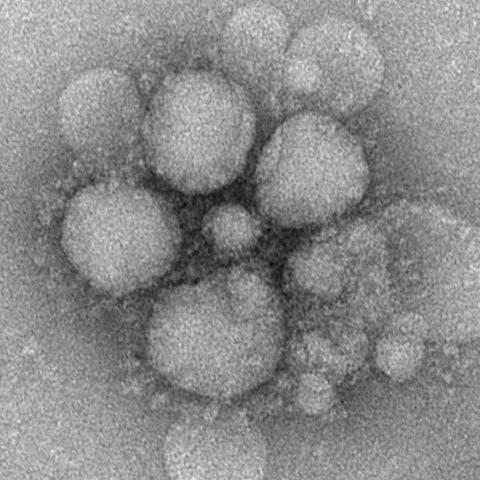

Camel urine has been used in the Arabian Peninsula as a part of Islamic prophetic medicine. This has, in recent years, been linked to the spread of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), AKA camel flu, a viral infection caused by the MERS-coronavirus. A team of researchers from King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, claimed to have extracted from camel urine a possible treatment for cancer: PMF701. This research was published in an article titled ‘Camel urine components display anti-cancer properties in vitro’. Permission to conduct studies on humans was not granted by the Saudi Food and Drug Authority. Numerous scientists and doctors within the region have denounced camel urine’s additional medicinal properties, rejecting such claims as figurative piss.

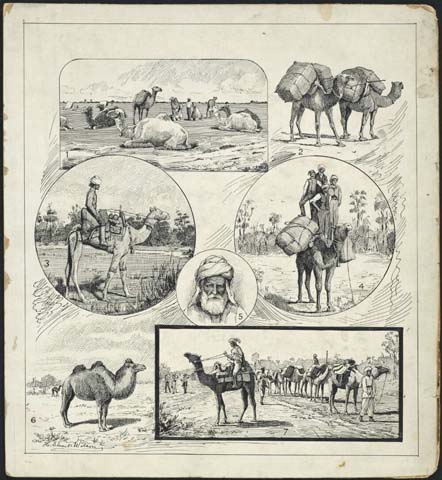

The She-Camel of Australia

![(1901) ‘Afghan and Decorated Camel [B 14739]’, General Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1901) ‘Afghan and Decorated Camel [B 14739]’, General Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image53.jpg)

In my name, Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Master of the Day of Judgement.

So they say. So some believe.

All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds.

Or at least, the World at a certain glint. From certain viewpoints.

My voice speaks of all, for all, knowing all.

At least to some.

Surely those who disbelieve, it being alike to them whether you warn them, or do not warn them, will not believe. Allah has set a seal upon their hearts and upon their hearing and there is a covering over their eyes, and there is a great punishment for them.

Or perhaps not. Perhaps that is not true.

This Story, there is no doubt in it, is a guide to those who guard. For all and some. For those who wish to read and perhaps even for those who do not.

A tale revealed to you—so let there be no straitness in your breast on account of it—that you may warn thereby, and a reminer close to the believers.

![(1870) ‘Afghan camel drivers [B 61979]’, Beltana Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA. (1870) ‘Afghan camel drivers [B 61979]’, Beltana Collection, State Library of South Australia, Adelaide, SA.](img/docmedia/image54.jpg)

Let the omniscient knowledge and judgement come forth. Or if not, let it simply be a tale of cameleers in أستراليا and nothing more. Praise be unto them.

And so to Adelaide was sent the trained Imam, from Sarajevo where he had previously enlisted in the Yugoslav Army, before which he had been incarcerated by Nazis in a place named Stalag 17 based in Bosnian lands.

Escaping to Brno, the trained Imam then sailed for twenty-six days from Napoli to Melbourne, on a ship where he was the sole Bosnian.

From Melbourne he transferred to Bonegilla, to a migrant settlement camp, seeking halal foods from Albanians, which were shared with Russian and Romanian Muslims.

Upon hearing of the death of an Afghan Cameleer who had financed the construction of a Mosque and served as Mulla, the trained Imam travelled to this Mosque in Adelaide.

Upon visiting the Mosque, the trained Imam noted the congregation small. Only seven attended Eid prayer. All were elderly, retired cameleers. Four lived at the Mosque. What was typically a cause for celebration, had a sombre tone.

Following the service, the trained Imam escorted one of the elderly cameleers to the graveyard. The man was from Kabul. He was frail and needed assistance. He stood before one of the graves for some time. The trained Imam did not ask the elderly cameleer who had died, or what he was thinking.

When they returned, the trained Imam helped the former cameleers prepare bolani. After prayer, they ate in silence.

After dinner, the trained Imam cleaned the plates, and assisted the men to their beds. The elderly cameleer appeared troubled. The trained Imam queried: what is the matter?

The elderly cameleer shooed the trained Imam away.

In the evening, one of the Mosque’s volunteers, a Romanian Muslim, approached the trained Imam: the old man, the cameleer, he is troubled by the tale of نَـاقـة الله, the She-Camel of God.

And to Samood was sent their brother Salih. He said: O my people! serve Allah, you have no god other than Him; clear proof indeed has come to you from your Lord; this is as Allah’s she-camel for you-- a sign, therefore leave her alone to pasture on Allah’s earth, and do not touch her with any harm, otherwise painful chastisement will overtake you.

The volunteer continued: He fears that as one who devoted his life to guiding camels, that have now all but served their purpose, he is as the tribal leaders that refused to listen and hamstrung the camel.

So they slew the she-camel and revolted against their Lord’s commandment, and they said: O Salih! bring us what you threatened us with, if you are one of the messengers.

The trained Imam responded: that is a misguided fear and a misinterpretation of the Nobel Quran.

The volunteer said: I have told him as much, but he remains grief-stricken.

The trained Imam said that he would try to console him, but the volunteer insisted that no amount of consolation would change the man’s mind. The trained Imam nodded in understanding. He was new and younger, and had yet to earn the man’s respect. Linked with respect was an ability to comfort.

And, the trained Imam knew, comfort was hard to bestow in these times. There was great hatred for these men. At this Mosque, on Little Gilbert Street in the city of Adelaide, many wished that this Mosque, that these Muslims, would disappear.

Such was this nation’s foundation, since federation in 1901: that the skin of its inhabitants must be light. Furthermore, they must speak not only the English language, but all European languages.

3. The immigration into the Commonwealth of the persons described in any of the following paragraphs of this section (herein-after called “prohibited immigrants”) is prohibited, namely: –

(a) Any person who when asked to do so by an officer fails to write out at dictation and sign in the presence of the officer a passage of fifty words in length in an European language directed by the officer;

(b) any person likely in the opinion of the Minister or of an officer to become a charge upon the public or upon any public or charitable institution;

(c) any idiot or insane person;

(d) any person suffering from an infectious or contagious disease of a loathsome or dangerous character;

(e) any person who has within three years been convicted of an offence, not being a mere political offence, and has been sentenced to imprisonment for one year or longer therefor, and has not received a pardon;

(f) any prostitute or person living on the prostitution of others;

(g) any persons under a contract or agreement to perform manual labour within the Commonwealth: Provided that this paragraph shall not apply to workmen exempted by the Minister for special skill required in Australia or to persons under contract or agreement to serve as part of the crew of a vessel engaged in the coasting trade in Australian waters if the rates of wages specified therein are not lower than the rates ruling in the Commonwealth.

The trained Imam had a reverence for the texts that guided men. This text he considered most foul. Yet despite this, he agreed to travel to these lands. Such were the turbulence of the times they were in.

His comparatively paler skin, the trained Imam suspected, was how he had managed to arrive, and how these cameleers’ colleagues and families had not.

Not sin or camels, but this deeper-rooted problem, the trained Imam believed, caused the elderly man’s grief.

This same hatred permeated Europe and the hearts of those that had imprisoned him. The hatred was not identical. It was improper to equate the two. But it was also improper to see zero similarity.

This hatred had failed in Europe. As such feelings would fail here, believed and knew the trained Imam.

The trained Imam told the volunteer: Comfort can come in many forms. In the form of food, and care, and treatment. If we cannot solve matters of the soul let us strive to solve matters of the body. We will care for these men as they cared for camels.

And in so doing, the trained Imam believed, would eventuate a time in which men like this would not fear death as this man did.

Since camels were domesticated millennia ago, their milk has sustained numerous nomad and pastoral cultures. In harsh environments, camel herders have survived solely on milk.